This is a story of data traveling through time, which is appropriate, since it’s about William Gibson, the man who turned data into a place, a space—cyberspace.

This is a story of data traveling through time, which is appropriate, since it’s about William Gibson, the man who turned data into a place, a space—cyberspace.

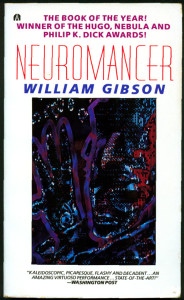

In 1985, I was 25 years old and had given up what I thought childish things. Specifically, science fiction. I’d read SF from childhood through my teens and young adulthood, and I’d come to the conclusion that Heinlein, Bradbury, Asimov and the other giants had shown me the mountain tops. The new writers coming along wouldn’t take me anywhere really new. (This was presumptuous and false, but that’s where I was at.) I was also in the middle of my march to greatness as a reporter (another false assumption) and my reading time was filled with tons of journalism.

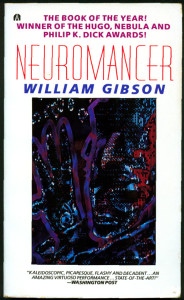

I worked in the New York bureau of The Hollywood Reporter, which was located on the 19th floor of the Paramount Building in Times Square. Our seedy offices could easily have doubled as the place of business of a $50-a-day-plus-expenses PI. One day in ’85, one of the co-founders of Cabana Boy Productions came into those offices to pitch a story. He was literally a cabana boy, or had been, to a rich Long Island dentist and his wife. The wife and the cabana boy had gone into the film business together with the dentist’s money and optioned Neuromancer by William Gibson. He gave me a copy of the book, which, having banned myself to ignorance, I didn’t know about. It had won all three of the top prizes in science fiction for first-time novelist Gibson. I decided maybe it was time to check out science fiction again. I was transported by the story in a way I hadn’t been since my teens. I gave up being snooty, bought each book Gibson put out and his and science fiction by other authors returned to my reading mix.

The impact of Neuromancer is hard to calculate. It changed science fiction. The movies. The cultural view of the digital world. As the book celebrated its 30th anniversary of publication last year, many have tried, some in essays better than I would be able to write. Gibson coined the term cyberspace, but more importantly defined the idea as a “consensual hallucination” where “console cowboys” (aka hackers) jack in and swoop through data arcologies, glowing, neon landscapes of information and power. He did this when the Internet was still nothing more than an email protocol used by the Defense Department. Many programmers admit they read the book and then spent all their time trying to make Gibson’s fiction a reality, ignoring the irony that his world is a dystopia, albeit a very cool, action-packed one. Hollywood got in on it too. “Matrix” owes everything to Gibson. It’s not the only film.

Fast forward nine years forward from 1985. I’m living in London. I score a magazine interview with Gibson, who’s promoting his latest novel, Virtual Light. I spend a great afternoon asking about the book that brought me back to science fiction. I turn the piece in. And the magazine spikes it. They’d decided to go in the dreaded a different direction that month.

Fast fast forward again—21 more years. I’m plowing through files on my computer. I’ll admit I’m obsessively organized, but I’m not a hoarder. When I get a new computer, I only move over the stuff I really need to keep. Over those 21 years, I’d moved the William Gibson feature from computer to computer so I now found a Microsoft Word icon so weirdly out of date and odd looking, it was like a fossil from, in Gibsonian terms, an earlier data arcology. I couldn’t even get Word to convert it until the most recent edition of the program came out.

I’m going to publish the feature here, not changing anything from that final 1994 version, so it might have the full impact of a story that traveled that far in time. Some things may be out of date. But none of Gibson’s observations are. Read as he invents Google Glass for Google before there was a Google.

In parting, a note if you need further proof of Gibson’s lasting contribution to the culture: the current issue of The New York Review of Books reviews Gibson’s newest book, The Peripheral. That publication reviews science fiction books about as often as I read any of the other books they cover.

My 1994 feature story:

William Gibson ushered us into the small mirrored elevator to go up to his room in the Franklin Hotel. The doors didn’t shut. After a few seconds, Gibson reached down and pushed one of the buttons on the control panel. The elevator’s doors stayed open. Gibson pushed the button again.

“Maybe there’s too much weight in here,” he said. There were three of us in the elevator, none of us that fat. And the doors still weren’t closing.

He pushed the button again. It was then that I realized I was going to have to tell one of science fiction’s reigning geniuses, the man who invented a future world of cyberspace cowboys and globe-spanning digital data nets, that the reason nothing was happening was because he was repeatedly pushing the wrong button. I pointed out the “door close” button was the other one, the one with the little sign — icon even — for two elevator doors coming together. The doors slid shut and we were on our way.

William Gibson defined the new wave in science fiction — nicknamed cyberpunk — with his first novel Neuromancer back in 1984. The nickname may have lost its edge now that its even being used by Billy Idol as the title for his newest album, but the ideas haven’t. In Neuromancer and the two novels that followed, data junkies “jack into the net,” a three-dimensional world where information is represented by glowing structures, shapes and pathways. Console cowboys hurdle through cyberspace, hacking their way in and out of corporate databases. If you watched the film “Lawnmower Man,” you saw a glimpse of the cyberspace Gibson writes about, even conceived. In his world, giant multinationals kill for the right bits of data, female assassins sport retractable razor claws and folks regularly stick chips into slots in the back of their heads to learn a language, or just get high. Gibson’s books are about social collapse, physical mutilation and techno overdrive.

He’s provided another look at that world with his new novel Virtual Light. It tells a story of the near future — nearer than the earlier three books — that is at once more human and more realistic than his earlier work. But the elevator episode should really come as no surprise to those who’ve followed his career: Gibson is concerned with the technology that may come, rather than the technology that is. He doesn’t use electronic mail or trawl the pathways of existing computer nets. He only started working on a computer when he was in the middle of his third novel — up until then he wrote on an ancient Swiss-made typewriter.

“I don’t know, I think I would get squashed by the incoming e-mail, or the time I’d spend just flipping through it to try to see if there was anything there, ” Gibson says. “I have to sit in front of this computer all day. The last thing I need is to be connected to this network.” But he likes what the networks represent. “Basically, people are kind of doing this cracker barrel routine. They are just sitting around chewing the fat. It’s incredible. These guys in Texas are chewing the fat with people in Helsinki and Moscow simultaneously. That’s very appealing. But I just think I don’t have the time. Maybe when I’m older, when I retire, and when the interface technology is infinitely more elegant.”

The author who first described much of what today’s virtual reality pioneers are still trying to invent has only used a VR rig once. For a half hour. But Gibson has strong views on where VR is headed. The helmet-and-gloves set-ups in use today are already antiques, he says. “My real hunch on VR is that all of those gloves and goggles — and all of that stuff the Sunday magazines all over the world have been telling us is the VR for so long — it’s started to look old-fashioned, started to look kinda quaint. That stuff is going to be like all of those wonderful Victorian gizmos that immediately preceded cinema. I think the drawings of pretty girls in goggles and gloves are going to go right into the kitsch classic category of sci-fi future imagery. And what we actually get as virtual reality is something much spacier.”

Something perhaps like the Dream Walls described in Virtual Light. These let people sculpt 3-D holographic images that they can see and others can look at from different angles, without the aid of helmets or goggles. Or if we do have to wear anything, it won’t be a helmet, but the pair of Ray Ban sunglasses that the characters in Virtual Light are killing each other to possess. In the novel, the glasses can pump “virtual light” directly into the brain via the optic nerve. One scientist Gibson’s read up on claims such a device would let us see the real world and things that aren’t real at all, side-by-side. Hallucinations would become reality. “So that everybody can walk around in the environment with the glasses on,” explains Gibson, “basically in Tune Town. You’d be walking around with Bugs Bunny and Jessica Rabbit and all these characters. We’d all be wearing the glasses, and we’d all see the characters from our perspective. And we’d all be seeing them do the same thing.”

Now that he’s written about it, someone will probably try to invent it. The odd — even scary — thing about Gibson’s writing is that his biggest fans want to create the dystopian worlds he describes — something akin to lovers of George Orwell forming a political party to get Big Brother elected.

“It baffles me,” Gibson says. “I spend a lot of time in interviews with people like that, trying to disabuse them of this tendency. It’s just baffling; I’ve come to the conclusion that a lot of people who read — I don’t know if it’s people who read science fiction or people who just have a particular interest — are completely deaf to metaphors and irony. They just don’t know what that is!… There are lots of people in the United States who just don’t get irony; irony just doesn’t register.”

Or maybe Gibson made it hip to be square, and readers identify with that. Matt ffytche, writing in The Modern Review, said, “The real breakthrough of cyberpunk writers such as William Gibson was in meshing street talk with electronics jargon to produce an inconceivably hip image for computer buffs, In reality, the closest any of its readers get to inhabiting electronic space is a fractal T-shirt.”

Gibson laughs, calling the comment “cruel, cruel,” then adds, “There’s something there, yeah. I don’t necessarily agree that was the real achievement. It was a breakthrough to some of these guys to realize that, they too, could wear a leather jacket.” Then he points to Case, the drug-addicted console cowboy in Neuromancer. “I wouldn’t want to run into Case. He’s a sociopath. He’s so badly addicted that his pancreas is going to fall out in the next 15 minutes. I thought I’d made it abundantly clear that this guy’s relationship with cyberspace was pretty problematic.”

Addicted sociopaths don’t come to mind sitting in Gibson’s small hotel room in South Kensington. High tech it isn’t. He is silhouetted against the window, behind him Victorian red brick houses across the street and in the nearer-distance the hotel’s Union Jack hanging from a flag pole bolted to the outside wall below the room’s window. He looks the author in beige chinos, a dark Levis jacket and trademark small round glasses. He’s almost professorial in demeanor, spinning tales in his quiet Virginia accent.

The whole look seems out-of-place when the conversation turns to new-tech weapons of personal destruction. Like any Gibson novel, Virtual Light is a thriller as well as a glimpse into the future. The story is punctuated with high-impact gun battles whose realism is assured by Gibson’s diligent weapons research. His approach is take what is possible now, set in the future and then try to scare us with it.

Berry Rydell, the ex-cop and sometime security guard who is Virtual Light’s protagonist, drives a Hotspur Hussar, patrolling the Los Angeles neighborhoods that can afford private policing. The vehicle may seem incredible, advises Gibson, but it “is what the British troops in Northern Ireland toddle around in. It’s an exact model, with the electrified bumper. That’s just taken from a book on riot control technology, as is the Israeli gun that fires recycled cubes of rubber tyre.”

In the novel, the latter is aptly called a chunker. And the ultra deadly handguns in Virtual Light are simply the next generation of military small arms, again all researched by Gibson out of catalogs and magazines. “The bullets — some of them are square — they’re not even bullets. They look like wax, hard wax crayons, that project over the side of this solid piece of explosive — a thing like a nail, like a machine gun firing these huge nails. The projectiles just pour out of one of those things like a stream of water. You could cut cars in half just like — whoosh!” he finishes with emphasis.

Gibson’s crackling mix of weapons, weird tech, next-century street talk and computer warriors would seem ready-made for Hollywood moguls looking to make the next “Terminator II” or “Total Recall.” Yet so far, a Gibson story has yet to make it to the screen. That will all change soon because a British production company has shot a short film based on Gibson’s story “The Gernsback Continuum.” Channel 4 will broadcast it.

Gibson has just seen a screening of the short while on his visit to London, and he’s pleased with the film, pleased as a kid on Christmas morning. “It’s a hip thing. They did a wonderful adaptation for the story. It’s almost entirely my writing, which is an incredible kick, and I didn’t even have to write the screenplay. The other bits are dialogue which are taken straight from the story.”

The first Gibson story to hit cinema screens will probably be an adaptation of his short story Johnny Mnemonic. He has written the screenplay and one star has already been signed. It’s set in a world without guns. One guy — a gangster — has the last .357 magnum, and that’s locked away in a vault. “All the other combat sequences are executed with this variety of spring-loaded, compressed air weapons.”

The so-called Sprawl trilogy of books that made Gibson famous — Neuromancer, Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive — are all optioned out to different Hollywood companies. None seems near getting in front of the cameras. Abel Ferrara, who directed The “Bad Lieutenant” and a new version of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” is developing another Gibson story, “New Rose Hotel,” as a feature.

Gibson has had a mixed experience with the movie business so far. He took a year and a half off from novels to write screenplay adaptations of some of his own stories. He was also one of many to get a crack at the script for Alien3, a film whose development and production was more tortured than its hero Ripley. A dozen or so writers worked on the script before shooting started. In the end, Gibson was turned off by the Hollywood approach: five or six people telling him what to do, so he ends up writing something no one’s really happy with.

Gibson’s own tv viewing — he subscribes to cable in Canada — is an eclectic mix of Canadian broadcasts, the BBC World Service and a daily dose of news, Japanese-style. He catches a newscast from Tokyo, in English, every morning at 11 am. “You see what happened that day in Tokyo, all the crime stuff, and everything. You kinda get inside what’s going on.” The Canadian version of MTV, called Much Music, brings him videos, including the Québécois pop music of French Canada, a genre he heartily endorses.

“Have you seen Québécois videos?” he asks. “They really ought to show them here — maybe they could show them here with different music. They’re kind of like the tabloid girls gone to video. They’re ridiculously up-front, super-soft porno, set to often totally wacky Québécois music that sort of sounds like Eurovision song contest stuff in French.”

The show that’s most affected the new novel is Cops, the grit and edge reality program that video tapes the activities of American policemen. The show’s view of cops doing a tough job helped Gibson create the character of Berry Rydell. The book even contains a futuristic version of the show called Cops in Trouble.

“I got a sense that the show gives a different, a kind of funky, down-to-earth sense of police procedure,” Gibson says. “It’s these poor crazy guys having to go out — guys with a bad job. I can’t imagine that it’s entirely honest, because they are invariably presented in quite a positive light. But it’s very hard to watch without gaining some sort of image of people who are doing just an ugly job that has to be done.”

And in the future of William Gibson’s imagination, ugly is just the beginning.

I just came around the railing and thought I saw Jake at the bottom of the stairs. Or maybe expected to see him. For an instant he was there. Sitting. This keeps happening. A shadow across the bed. It’s Jake. It’s not. He’s on the other side of the front door as I unlock it. He’s coming into the office to check on me, as he always did. I turn my head. Dark, empty doorway.

I just came around the railing and thought I saw Jake at the bottom of the stairs. Or maybe expected to see him. For an instant he was there. Sitting. This keeps happening. A shadow across the bed. It’s Jake. It’s not. He’s on the other side of the front door as I unlock it. He’s coming into the office to check on me, as he always did. I turn my head. Dark, empty doorway. “A fast-paced, deeply entertaining and engrossing novel. Last Words is the first book in a mystery series featuring the intrepid investigative reporter. Readers will be glad these aren’t the last words from this talented author.” —Robin Farrell Edmunds, ForeWord Magazine

“A fast-paced, deeply entertaining and engrossing novel. Last Words is the first book in a mystery series featuring the intrepid investigative reporter. Readers will be glad these aren’t the last words from this talented author.” —Robin Farrell Edmunds, ForeWord Magazine This is a story of data traveling through time, which is appropriate, since it’s about William Gibson, the man who turned data into a place, a space—cyberspace.

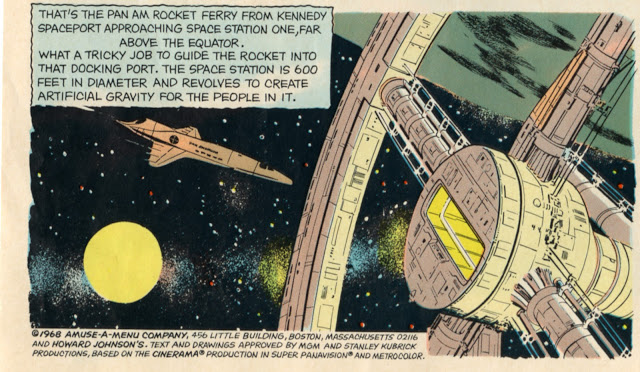

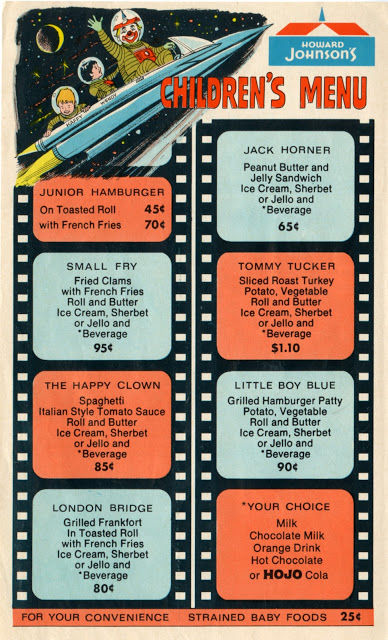

This is a story of data traveling through time, which is appropriate, since it’s about William Gibson, the man who turned data into a place, a space—cyberspace. Collisions that happen in my mind: “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Interstellar” and Howard Johnson. Okay, the first two are obvious for the way the first movie informed the second. (How many “2001” references did you count in “Interstellar”?)

Collisions that happen in my mind: “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Interstellar” and Howard Johnson. Okay, the first two are obvious for the way the first movie informed the second. (How many “2001” references did you count in “Interstellar”?)